For a little under a year, I’ve had the pleasure of serving as product manager for Mapzen Search, working with some of the most brilliant folks working in mapping today as we build a world-class open source geocoder1 and a remarkable service open to all on top of it. Not to mention playing a small part in many of the other incredible things we do at Mapzen. So it’s incredibly bittersweet for me to share that I’m stepping way from the Github issues and leaving Mapzen for the Brown Institute for Media Innovation, a joint research center between Columbia School of Journalism (where I’ll be based) and Stanford’s School of Engineering, as their Chief Technology Innovation Officer.

When I joined Mapzen, it was because I was getting the chance to join a remarkable team, working to create a thing I thought needed to exist. I wanted a better open source geocoder because I wanted to use it on my own data, well really the data of many New York Cities past. My former team at The New York Public Library needed a geocoder for historical New York City, and Pelias seemed like the right tool to make that happen. We haven’t built an open source historical geocoder out of Pelias2, but we’ve been working on a whole lot more that makes world class geodata accessible to everyone.

We created Who’s on First, an open data gazetteer that’s already the single best place to list and connect all of the places.

We sponsored Libpostal, the first open source worldwide address parser based on statistical learning that can make sense of nearly any address from anywhere.

We built Eraser Map, a mapping app that doesn’t track you, a remarkable achievement.

But Mapzen’s always been about more than just writing open source mapping software. There had been plenty of good open source mapping software before OpenStreetMap just miracled into existence. But what OpenStreetMap catalyzed was the synthesis of open source and open data created by open communities. Now, for the first time, there were opportunities for people to map the world, to create the tools to create the data that those communities could collect. And for the first time, companies and regular people could collaborate across open data projects to do what had before been the sole jurisdiction of gods, kings, and generals: to try and see the whole world. And for the first time there was the ability for people to use these tools for self-representation.

What brought me to Mapzen wasn’t just the prospect of building these tools, but being a part of a place that wanted to make geo more open forever. Not just so that it’s free in cost, but free for all to use to advance research, to tell stories, and to be preserved so we can remember our present in the future. It’s all set forth in our Magna Carto.

We’ve come a long way over this past year. And I can’t wait to use what we’ve made. I suspect a lot of others will as well. But the truth is, this doesn’t happen alone. Mapzen’s all about building communities to build open data and open tools. They want to do it with you. And I’m excited to help from the outside. Hopefully you are too. The work we do here means the world to me. Literally.

Onward, together. This is going to be fun!

p.s.

You know where to find me:

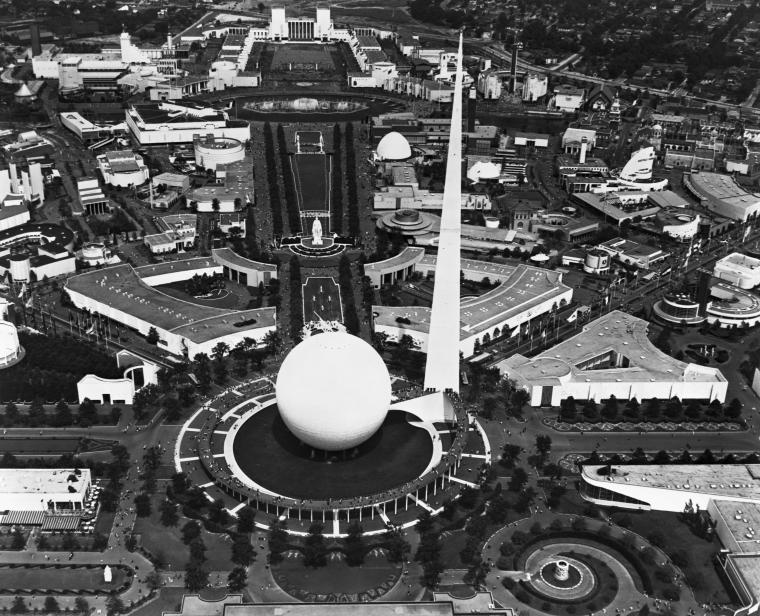

Image: Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. (1959 - 1971). Aerial View of Perisphere Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/917c3c71-b8ff-5589-e040-e00a18067ba2