The original publication of the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) in 2006 massively increased the availability and accessibility of transit data, and enabled countless new applications of this data for routing, spatial analysis, and city planning. A decade later, the historic collection of published feeds is also a valuable resource for understanding how transit systems evolve over time, and how service and investment decisions can shape our transportation choices and the built environment.

GTFS Data Exchange, a project started in 2008 by Jehiah Czebotar with just a dozen feeds, was one of the first compilations of public feeds and archived data, and eventually grew to approximately 1,000 feeds, with over 13,000 archived feed versions totaling 93 gigabytes.

GTFS Data Exchange entered read-only mode in 2016, with Transitland becoming one of the services to take its place as an ever-updating archive of feeds. This summer I began a project to import some of GTFS Data Exchange’s historical feeds versions that predate Transitland into the Transitland Feed Registry, and to use this combined data to better understand how often feed updates are published, the amount of time covered by each schedule, and trends in how much transit service is provided by each operator.

Retrieving information from GTFS Data Exchange

Since GTFS Data Exchange was built from community contributed data, the quality of the data and the naming conventions was unstandardized. While some GTFS Data Exchange sources were easily matched with Transitland Feeds using simple searches (e.g. Caltrain has no name variants), others were unsearchable or duplicated in the database due to alternative names or acronyms (Bay Area Rapid Transit shortened to BART, for one).

In order to address this, I developed two conventions for identifying matches between GTFS Data Exchange and Transitland Feeds:

- A name search that identifies exact name matches

- Source match: where the feed URI for both sources matched exactly

This semi-automatic matching associated 311 out of 845 Transitland Feeds with their equivalent in GTFS Data Exchange, allowing me to upload about 3,000 historic feed versions that predated the creation of Transitland. We welcome others to help us manually associate additional feeds.

Historic levels of service

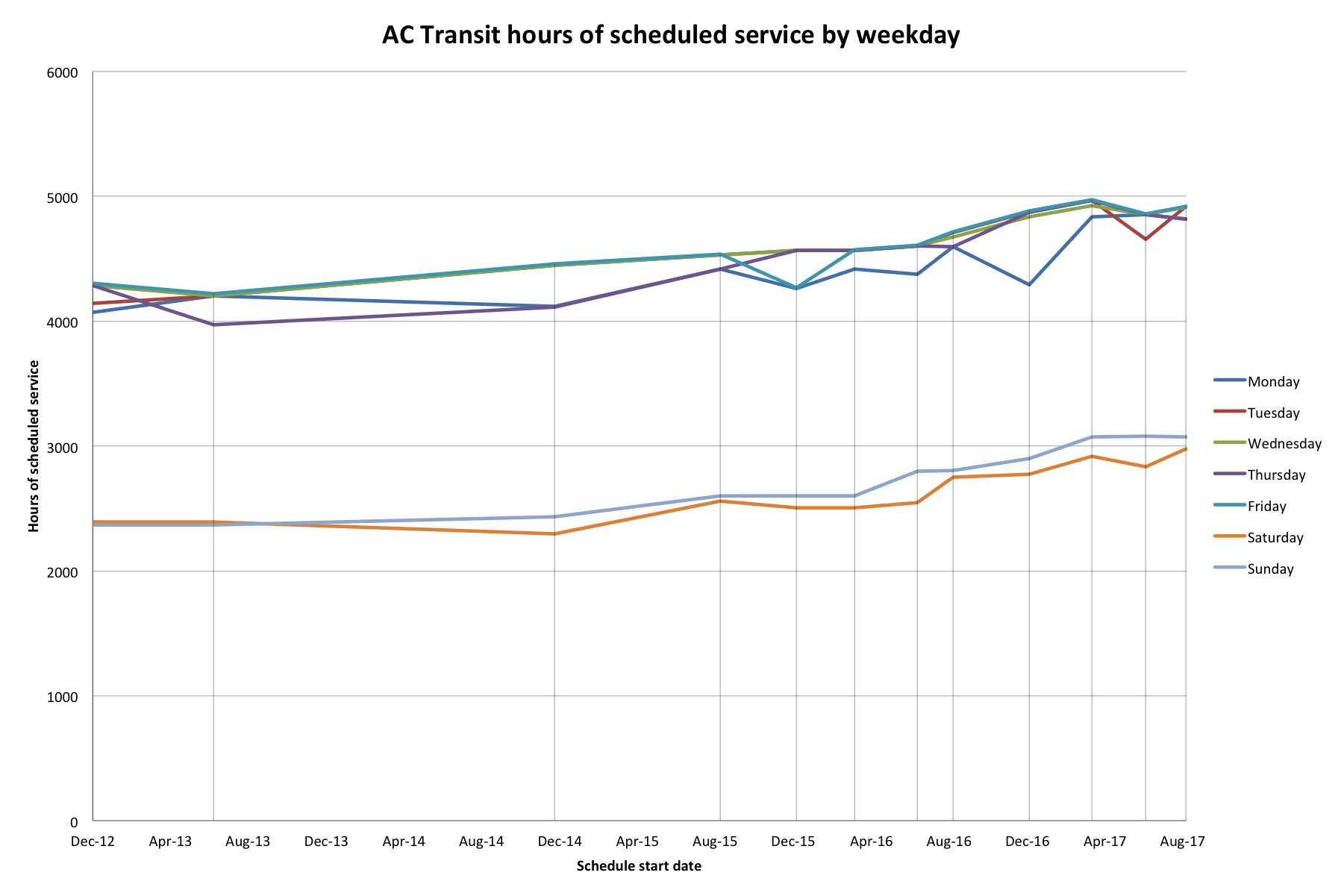

Whenever a new feed version is added to Transitland, several statistics are generated to help understand the contents. One way the feed version is characterized is to calculate the number of service hours for every day in the schedule. The addition of the historic data allows us to compare at the levels of service from several years ago to the present day.

This example from AC Transit, using feed versions from 2012-onwards, highlights a slow but steady restoration of service cuts made during the Great Recession, particularly in weekend service.

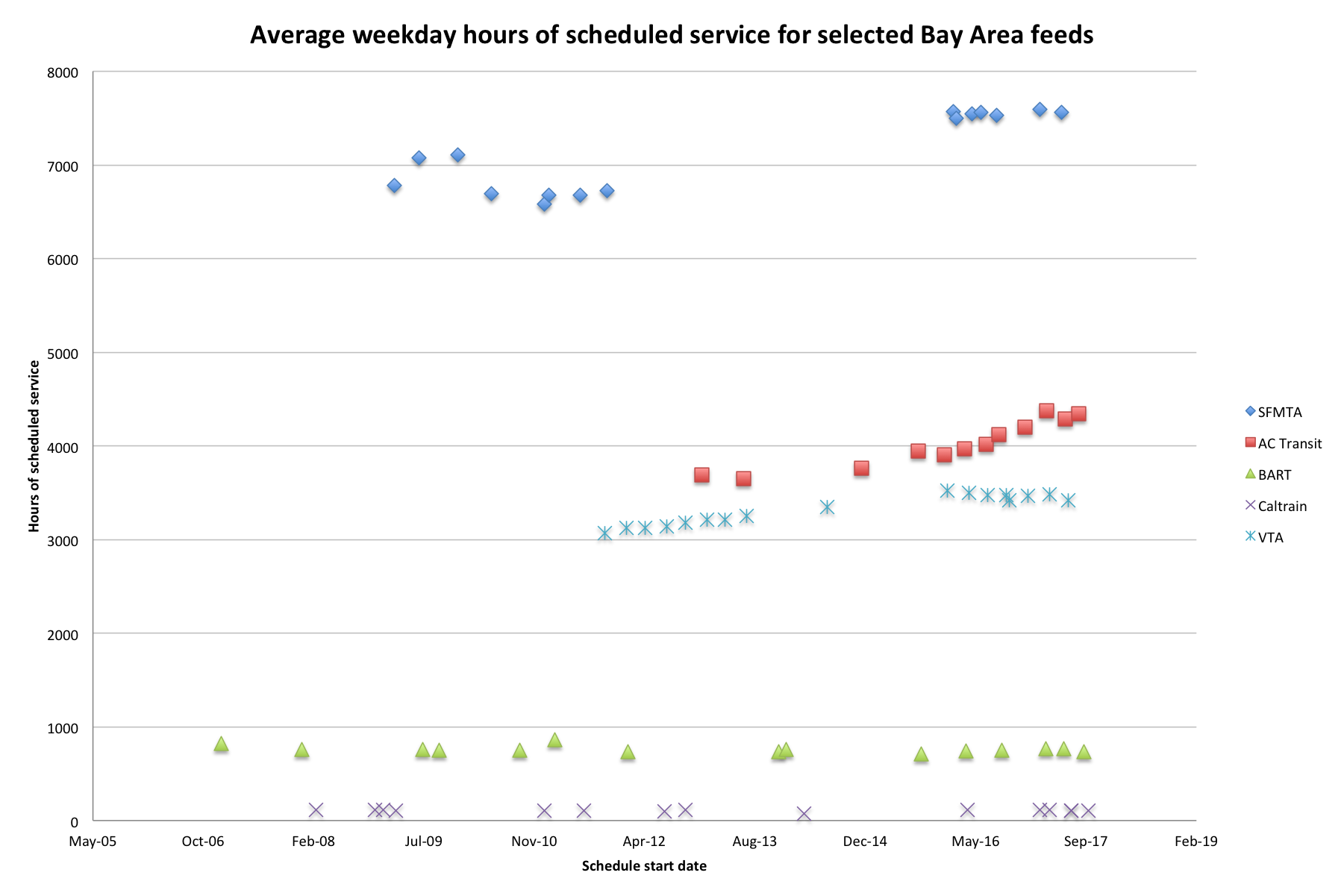

Comparing service hours over time in between different transit feeds also helps us understand the larger picture of the entire region. Policy changes could have shifted the level of service in an entire area, or budget realignments may have helped support the operating costs of buses, but not necessarily rails or ferries. For these use cases, I’ve aggregated the information provided above for each feed into an average service hour per feed version. Below is a graph including the Caltrain, BART, VTA, and AC Transit feeds.

Although there’s a large difference in the level of service hours between feeds, it’s important to recognize that routes can be vastly different and therefore it’s more valuable to compare relative, rather than absolute change in service hours. Here, we can see that since their first feed versions, AC Transit, Valley Transportation Authority (VTA), and San Francisco Municipal Transportation Authority (SFMTA) have all increased their levels of service, while BART and Caltrain’s service times have remained relatively level.

While it might be straightforward to make assumptions that more service means better service, that’s not necessarily the case. While the Caltrain and BART are regional rail systems that move their passengers long distances across the entire Bay Area, AC Transit, VTA, and SFMTA are all bus systems which prioritize coverage and accessibility within their particular cities of concern. The operating range and to an extent, frequency of the BART and Caltrain relies on a heavy investment in rail, whereas bus systems are more far flexible in experimenting with their routes and schedules.

Feed update frequency and duration

Another statistic this series of graphs revealed is the variation in frequency of feed version updates, which led to a few more exploratory questions. As we can see in Average Service Times in the Bay Area, some feeds update their feed versions more often than others. Does this mean we’re always using up-to-date information in these other feeds? How does the duration of each of these feed versions relate to the frequency of updates?

Transitland fetches the URL of each feed every day to check for new versions. Most providers publish updated feeds on a regular schedule, usually every few weeks to every few months, and follow the GTFS best practice of publishing a new feed before the current version has less than 1 week of service left. However, sometimes the current feed version ends on or before the start date of the next feed version — in other words, we’re using out-of-date information. In these cases, Transitland attempts to “fill in the gap” by extending the scheduled service in the current feed version, but this isn’t always accurate — they are, after all, just predictions. In order to represent updated information, we want at least a small overlap in the service period of each feed version.

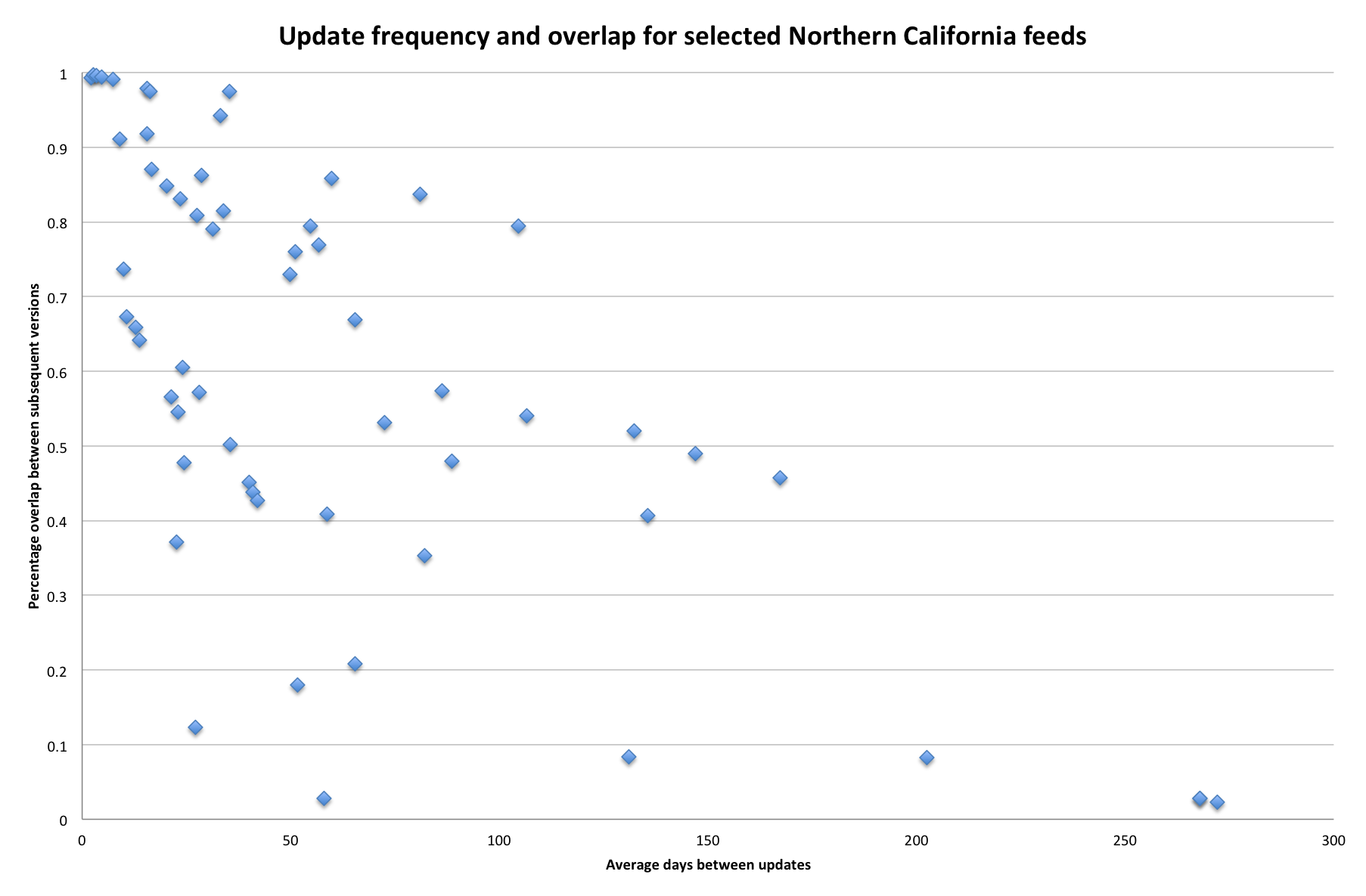

Here, for each feed in Northern California, we plot the average number of days between subsequent feed versions being published, and the percentage of schedule overlap (defined as the number of days shared in common as a percentage of the total time period covered by both versions).

We can see that frequently published feeds (as often as every day) tend to have a high degree of schedule overlap, whereas the least frequently published feeds (once or twice per year) tend to have less overlap. This suggests that feed consumers should take additional care with infrequently published feeds to prevent a lapse in scheduled service.

Update statistics in the Transitland API

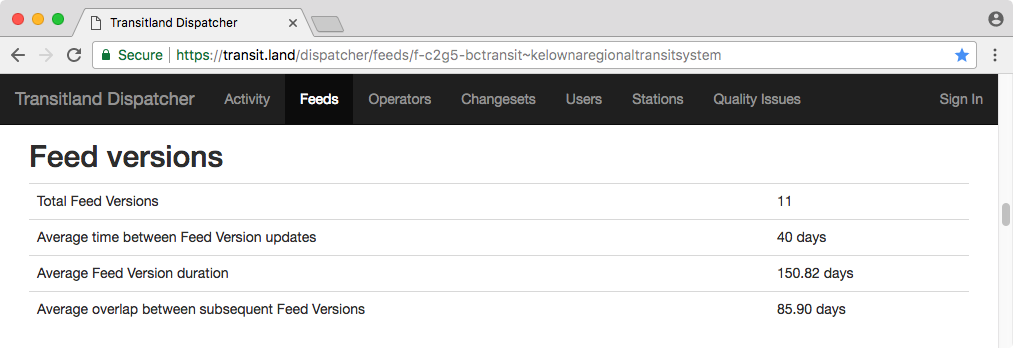

Statistics on feed updates can now be generated for each Feed using the Transitland API, and are also shown in the Dispatcher page for each Feed.

Conclusion

Our hope is that the availability of archival feed versions — some as early as 2008 — will enable researchers to answer questions about how transit systems change over time. We plan to continue adding more historic feed versions to Transitland and documenting this process on the GitHub repository for this project. We also encourage interested users to explore the archive and let us know what you discover. Finally, if you have historical GTFS feeds to contribute, please do drop us a line.